Traditional Chinese Pastries

The huge diversity of Chinese pastries in Singapore, ranging from kueh (sweet or savoury snacks) to biscuits and cakes, reflects the cultural traditions of the local Chinese community. These delicacies have been adapted over time to suit local tastes. For example, ingredients from the region such as pandan (derived from the Pandanus leaf) and kaya (coconut jam) have been added to recipes.

Kueh are made with rice flour, and usually have a sweet or savoury filling. Biscuits are made with wheat flour and lard, and may be filled with lotus paste, mung bean paste or red bean paste. The addition of lard gives these pastries a distinctive aroma and their characteristic flakiness. Other forms of pastries, such as xin ren bing (杏仁饼, almond cookies), do not contain fillings.

Geographic Location

Chinese pastries are made and sold in various establishments across Singapore, such as hawker centre stalls, neighbourhood bakeries, specialised shops, and even hotels and restaurants.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, establishments selling these types of pastries were initially set up by immigrants from China. The different dialect groups brought their own styles and specialities, ranging from the Teochew ngo sek teng (伍色糖, a set of sweets that includes bean paste pastry and sticky candy) and Cantonese sei sik beng (四色饼, a round pastry with bean paste or winter melon filling), to the Hokkien tau sar piah (豆沙饼 , flaky biscuits with mung bean filling) and Hainanese jian dui (珍袋, fried pastry made from glutinous rice flour and coated with sesame seeds).

The increasing commercialisation of the trade has meant that a significant amount of pastries today is produced by chains, both foreign and local, although independent and traditional businesses continue to be involved in the sector. The latter type tends to be family-owned establishments.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

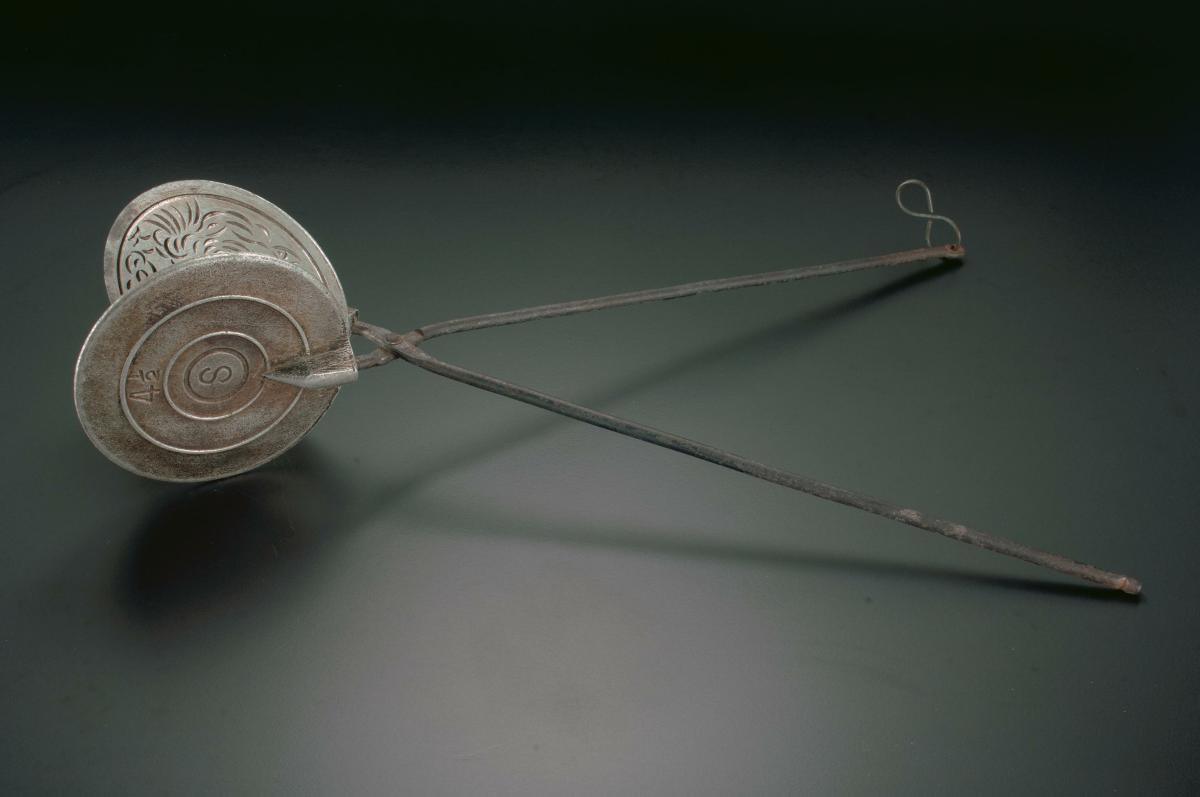

Old-style Chinese pastries are traditionally made by hand and are often inscribed with Chinese characters such as 囍 (double happiness) or 福 (prosperity). Some pastries are connected specifically to festivals and other important events, while some pastries are also prominent in religious rituals, with biscuits brought as offerings to the gods.

As part of Chinese wedding rituals, xi bing (喜饼) pastries are given to the bride’s family at the tea ceremonies by the groom as an appreciation for having raised the bride and as an announcement of the marriage. In the Teochew tradition, peanut and sesame brittles are given by the groom’s family at weddings: the candy signifies qian zi wan sun (千子万孙), meaning to bear many descendants.

The Hokkien community’s ang ku kueh ;(红龟粿), with its distinctive tortoise shell shape, is often presented to parents on their birthdays as a mark of respect. Mooncakes are traditionally consumed during the Mid-Autumn Festival, their round shape symbolising the unity of Chinese people and the wholeness of the family. Other pastries like love letters and peanut candy are popular during Chinese New Year.

Pineapple tarts which are enjoyed during the Chinese New Year, are associated with auspicious meanings, as the pineapple is known as “ong lai” in Hokkien, which literally means “the coming of fortune”. It is also a festive food that can be found during Hari Raya and Deepavali, reflecting the pastry’s multicultural roots. The ingredients reflect its Southeast Asian roots due to the use of spices such as star anise, cloves, and cinnamon. On the other hand, the tart’s buttery base, similar to shortbread, reflects its European roots.

Experience of a Practitioner

Madam Ang Eng Wah has been involved in the traditional Chinese pastry business since her parents started Poh Cheu, a shop selling handmade ang ku kueh and other pastries, when she was a child. A typical day for her begins at 5am, when staff undertake chores such as managing the inventory, frying ingredients and making fillings. By 9am, the first batch of kueh is ready for sale.

In the beginning, Poh Cheu’s kueh came in only five flavours: red bean, peanut, salted mung bean, durian, and yam. This has since doubled in response to customer feedback, and the shop now offers flavours such as green tea and sesame as well. But, some things have remained the same: the kueh are still made from scratch, and her parents continue to oversee the process to ensure the freshness and quality of Poh Cheu’s pastries.

Madam Ang remembers how her family gatherings used to centre on the making of ang ku kueh. She believes such traditions contribute to Singapore’s cultural fabric.

Present Status

The fact that many traditional Chinese pastry businesses are family-owned makes it harder for others to learn certain techniques and recipes. However, the growing corporatisation of the trade is likely to result in greater knowledge-sharing in the future. There are organisations that offer courses in Asian pastry-making and many recipes are available in cookbooks and on the Internet.

Ultimately, the sustainability of Chinese pastries depends on the younger generation’s willingness to enter the trade and adapt the pastries to modern tastes. The tight labour market and growing rental costs, alongside the long working hours, are challenges to overcome. There have been moves by some shops to attract younger consumers by marketing Chinese pastries as artisanal products and growing their online presence. Other shops have found new business opportunities, such as providing hotels with miniature kueh to use as alternatives to Western-style canapés or tapas.

References

Reference No.: ICH-087

Date of Inclusion: October 2019

References

Chan, Margaret. “Impress your folks with scalded dough pastries”, The Straits Times. p. 6, 6 March 1994.

Foong Woei Wan, “Wife cakes worth the wait”, The Straits Times, p. 82, 9 March 2008.

Quek, Eunice. “Taste of tradition: Teochew, Hainanese and Hokkien mooncakes”, The Straits Times, 2015.

Singapore Bakery & Confectionary Trade Association. http://www.singbake.org.sg/ Accessed 8 February 2018.

Slow Food Singapore. “Sze Thye Cake Shop” http://www.slowfood.sg/programs/heritage-heroes/sze-thye-cake-shop/ Accessed on 17 November 2017.